In communities everywhere, certain groups may be more vulnerable to adverse health, water, or climate impacts, for example due to greater exposure to air and water pollutants or less access to protective infrastructure. Almost one billion people in the world live in urban slums, and every fourth urban resident lacks access to improved water, sanitation, and durable housing, heightening their vulnerability to adverse health, water, or climate issues.25 Indigenous Peoples and local communities hold rights to more than half of world’s land mass, but legally own only 10 percent of the world’s land.26 These and other at-risk groups will not be able to benefit equitably from nature-based solutions that can improve health, provide refuge from heat or extreme weather, and improve access to water services.

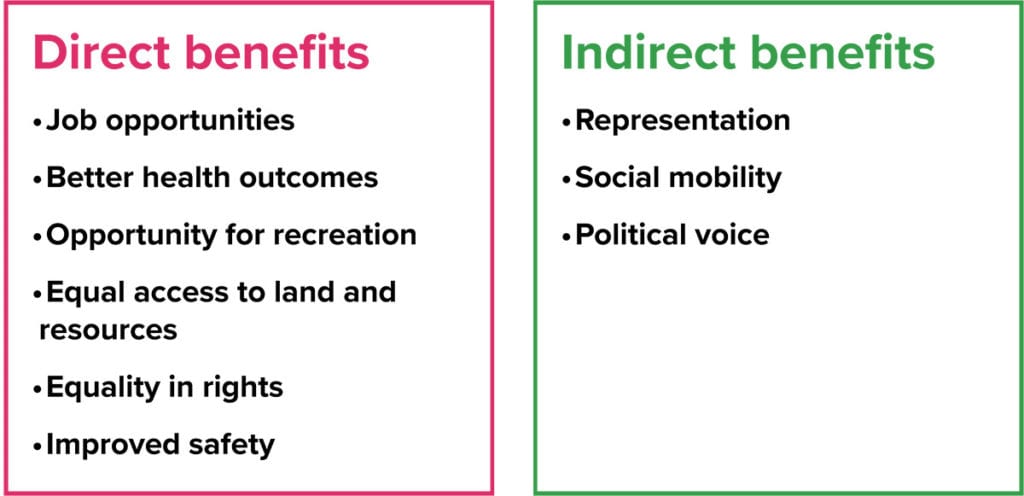

When social equity considerations are meaningfully incorporated into policies and plans, vulnerable communities can gain many direct and indirect benefits.22, 32, 34

For instance, the ‘One Soul One Tree’ campaign in Surabaya, Indonesia, launched by Mayor Rismaharini after her election in 2010, helped achieve twin goals of enhancing city forests and creating alternative means of income for local residents. It protected 5,000 mangrove trees and encouraged residents to harvest syrup and create products using the trees.

In Africa, the Green Belt Movement offers an example that combines forest restoration with community empowerment, particularly of women, to conserve the environment and improve livelihoods. The Green Belt Movement provides women with new income-generating and training opportunities, and includes them in planning and project activities related to climate mitigation and adaptation.