Wood Urbanism: The Power of Procurement for Forests

On 23 May 2019, Cities4Forests led an interactive workshop on “Wood Urbanism” as part of the Urban Future Global Conference that was held in the heart of Oslo, Norway – a world leader in both wood architecture and environmental conservation.

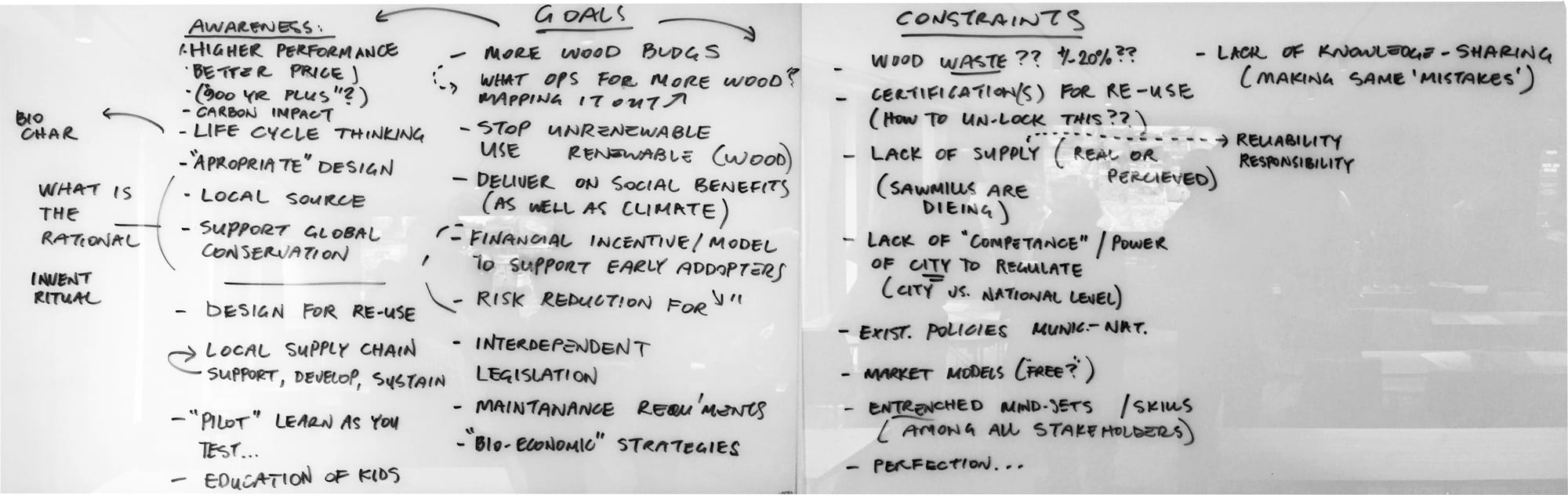

The goal of the workshop was to collaborate and exchange innovative ideas regarding how sourcing wood for urban development can help conserve and sustain forests. The workshop explored existing and new sourcing strategies for wood, which is a cutting-edge, climate-friendly building material poised to decarbonize the building sector and help cities meet carbon neutrality goals — if it can be properly linked to global forest conservation. Over 20 participants, including city officials, architects, representatives from the construction and forestry industry, sustainability consultants and media, gathered to innovate and identify opportunities and constraints to drive new climate and forest-friendly policy on wood procurement for cities.

Scott Francisco, a co-founder of Cities4Forests and founder of Pilot Projects Design Collective, opened with an overview of urban wood construction and its important role in meeting city climate commitments. Showing how wood can be used for everything, “from sky-scrapers to pot-scrapers,” he stated:

“Any city who wants to achieve carbon neutrality has to consider both wood and forests in their planning process. Wood is the only viable building material that sequesters large amounts of carbon, and forests are how the earth pulls CO2 out of the atmosphere. Sustainable wood sourcing can help us build low carbon cities and support global forest conservation.”

Participants noted that there are still major gaps between cities’ visions for sustainable procurement and their ability to specify wood products that meet the objectives; these gaps are common to cities around the world – from Olso to Vancouver to Quito. The workshop also revealed that many cities are eager to make changes to procurement policies. City representatives from six cities noted that they would like to see procurement policies that make it clear and straightforward to procure sustainable, forest positive wood.

Changing policy

Workshop participants participated in an activity to identify the kinds of changes that they might make in their cities actions to procure sustainable wood, grouped into “easy, medium, and dream big.” This collaborative activity highlighted the need to start with small changes to show early and immediate results, then build up to more ambitious changes in wood procurement policies.

The workshop provided a platform to exchange ideas and brainstorm new ways to incorporate wood and forest products into policy agendas. Participants also expressed challenges in existing policies and regulations that make sustainable sourcing difficult. Norway, for example, is highly advanced when it comes to forestry and innovative wood construction, having built the world’s tallest wood building. However, Norwegian participants pointed to a lack of investment in sustainable local forestry, limited access to Norwegian wood in local markets, and the need for local supply chains.

Some of the participants were interested in exploring the links between wood urbanism and the circular economy to understand how the power of urban consumption can benefit global forests, including forest carbon credits, wood procurement case studies and forest risk commodities. Other representatives from participating cities like Kochi (India), Guadalajara (Mexico) and Quito (Ecuador) described very different circumstances in their cities where the lack of local forest resources is the real challenge.

The way forward

Participants collectively identified constraints and ideas for moving forward. The discussion suggested that there are a number of ways to improve management of procurement, which are currently not fully employed. The mayor of Kochi, Soumini Jain, claimed the need for financial incentives or models to support early adopters. Can tax policies be made to encourage usage of more green material? What other financial benefits can we find?

In many countries, construction materials are regulated by national laws. There is thus a need to understand national policy and bridge levels of government to tackle this issue and enable a legal framework for wood. Cities are able to take a proactive role in this change as claimed by Paul Fuge, founder of Naturally Durable Inc., said that “the goal is to reorient existing administrative tools already well-developed within cities, to benefit the forests”. Sustainable wood sourcing can open opportunities for cities to build stronger regional relationships, set precedents for national policy, and establish innovative global city-forest partnerships.

Doug Smith (left) discussing with mayor Jain (yellow) and group dynamic during workshop (right). Photo: REVOLVE

Doug Smith, Head of Sustainability of Vancouver, highlighted the importance of establishing a long term view of wood in construction. “Vancouver requires high recycling rates for buildings that are taken down and for deconstruction as well. This allows for design strategies that take into account wood reuse and repurposing.”

Participants explored how the power of urban consumption can benefit global forests using forest carbon credits, wood procurement case studies, and forest risk commodities. The workshop also made clear the need for and value of communities of practice to support the growing inter-urban conversations on the benefits and implementation of sustainably-sourced wood in urban environments. This complex issue needs people representing multiple geographies and viewpoints, including those of producers and consumers. Stemming from this workshop, three global leaders in urban wood use – Vancouver, Portland, and London – will be working with us to host their own workshops on sustainable wood and procurement. We have to get this right. Wood is an essential part of our future on this planet, reconciling our need for growth with our need to combat climate change and deforestation. Having powerful cities lead, support each other, and share innovation will be key to its success.

“The exchange of experiences between other cities was very fruitful. I realized that in some Latin American countries we still have a long way to go in wood procurement. We need to focus where there are opportunities to intervene and work with authorities and the private sector to understand these key links in the value chain.”

– Veronica Arias, Former Secretary of Environment of Quito

The challenge for integrating wood procurement and certification in the circular economy is really about whether procurement strategies and certification can drive a market for reusing wood components for 2nd or 3rd generation construction. It was agreed that this would vastly extend the benefits of wood structures by keeping carbon sequestered even longer.

Participants collectively identified constraints and ideas for moving forward. The discussion suggested that there are a number of ways to improve management of procurement, which are currently not fully employed. Mayor of Kochi, Soumini Jain, advanced the need for financial incentives or models to support early adopters. Can tax policies be made to encourage the usage of more green material? What other financial benefits can we find?

In many countries, construction materials are regulated by national laws, so there is a need to understand national policy and bridge levels of government to tackle this issue and enable a legal framework for wood. Doug Smith, Head of Sustainability of Vancouver, highlighted the importance of establishing a long-term view of wood in construction: “Vancouver requires high recycling rates for buildings that are taken down and for deconstruction as well.’’ This allows for design strategies that take into account wood re-use and repurposing.

The need for local solutions was also highlighted – and the idea that wood urbanism can take many forms, and be suited to different contexts. As one participant put it: “Wood urbanism can set a more holistic socially-sustainable paradigm – not only to replace other materials, but as a driver for good development. Not everyone needs to build high-rises, whether they’re built from wood or not.”